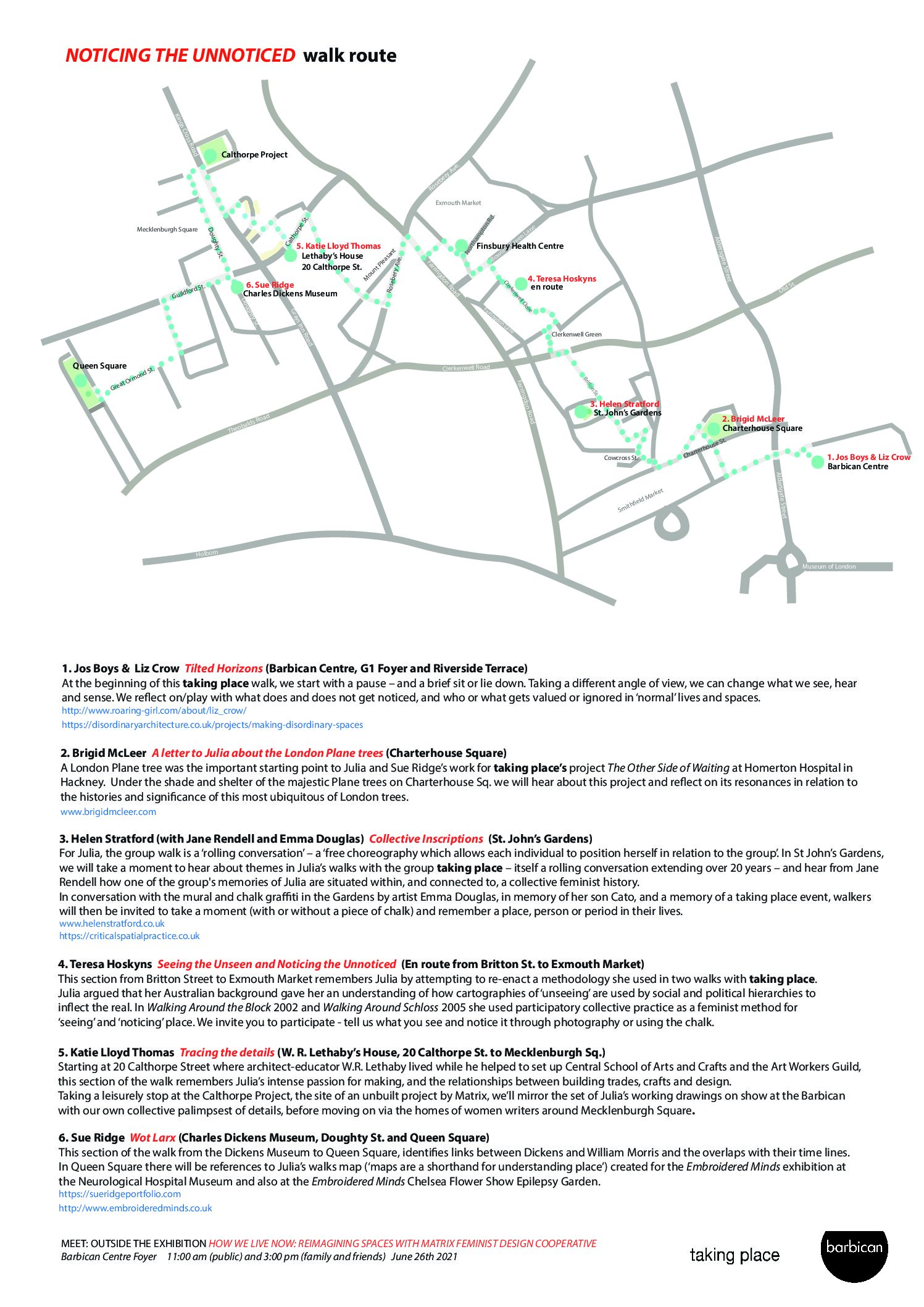

A public walk created by feminist art and architecture group taking place to accompany the exhibition How We Live Now: Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Cooperative, Barbican Centre, London.

taking place is a group of women architects and artists producing feminist interventions into public and institutional spaces in the form of events, installations, walks, conference presentations and publications. I was an active member of taking place between 2001 – 2010 and have contributed in other ways since then.

Julia Dwyer was member of Matrix feminist design cooperative in the 1980s and a founder member of taking place. Julia died in 2020 and on the occasion of the Matrix exhibition at the Barbican in London taking place produced this public walk in her memory.

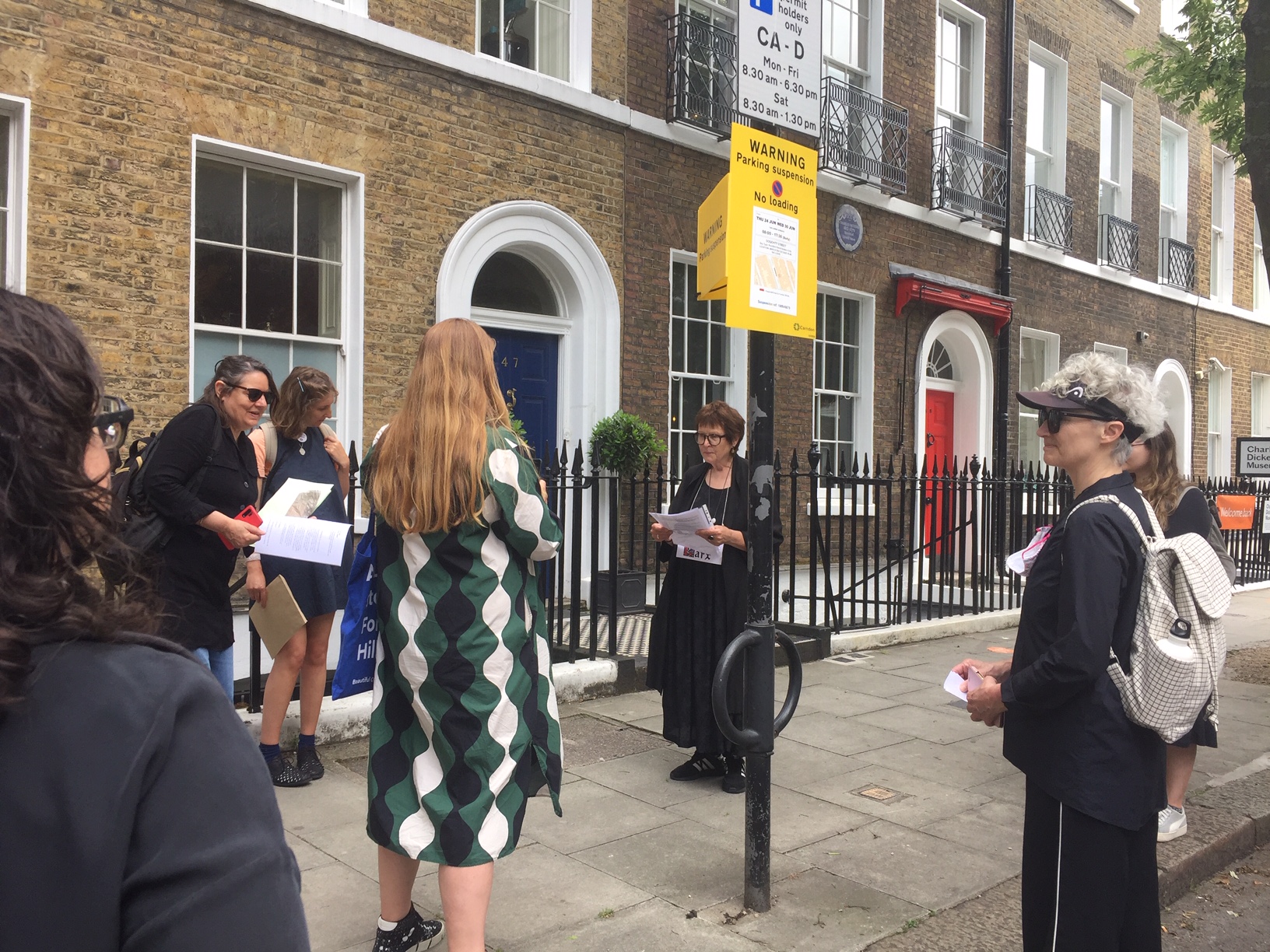

My own contribution to Julia’s walk was a piece of writing about the histories and spatial politics of London Plane trees. It took the form of a letter to Julia which I read to the group of walkers in Charterhouse Square, beneath the shade of some old London Planes.

Dear Julia,

Where are you?

I have started looking for you in the Plane trees. The London Planes. It seems a good place to start as they are everywhere in London. So perhaps my chances are good.

London has over 8 million trees, that’s pretty much one for every person who lives here. So perhaps to find you, I need to find your tree Julia. Or perhaps you might be found in exactly the opposite of such singularity, instead amongst the many.

Of these 8 million trees, the London Planes make up only 1.5%, yet they are the species, that have come to define the city, because, while prevalent in parks and gardens, such as here in Charterhouse Sq, they are most avidly street trees, road trees even. Planted with great fervour by the Victorians in the late 19thC, following the inspiration of the tree lined avenues of European cities, the Plane tree epitomises in London, an attitude to the city as a place in which to live well, potentially to thrive. A public place, of shared spaces, routeways and air. Of course, just like in Paris, their planting ‘en masse’ accompanied the clearance and demolition of slums, cloaked in a moral attitude that left little space or provision among the new council estates and their plane tree saplings, for the truly destitute. They were merely moved elsewhere.

Still as I cycled through Arnold Circus, one of the most well-known of such progressive council estates, on my way here from Hackney, it is hard not to see and feel in the wonderful mature Planes that round the circus, and the communality of the circus itself, the forward-thinking optimism of a form of city planning in which people, and what they need to live, are at its heart.

I am looking for you in the Plane trees Julia; maybe in one, maybe in a carefully tended cluster, on maybe in a stroll of trees along the Embankment. Maybe even here, in this square. Beneath the shade of these Planes. Tall, strong, immensely giving. Here with these survivors that have made the city their home.

Certainly I know for sure of one Plane tree that holds you. (It’s here in my hand). The Homerton tree. Even now, I can see you standing outside Homerton hospital beside a modest though much loved Plane tree that had to be felled to make way for a new maternity unit. We were there as ‘taking place’, our feminist group of women architects and artists working on a project that would have a permanent place in the new unit when it was built.

You and Sue became the champions of the Plane tree’s legacy; its transformation, from a great loss to the nurses, midwifes and mothers giving birth, as it shaded the hot wards in summer and shielded everyone from the view of the car park below, to a new and beautiful measure.

You and Sue decided to save the tree, or at least some of it, and its beautiful lacewood became a plane of plane – a ruler of sorts – installed in the new maternity unit in 2010. The lacewood ruler, known by you as ‘the Homerton measure’ was exquisitely marked with a range of measures vital to the process of giving birth: diameters of dilation, time between contractions, heartbeats per minute, and other statistics for the unit, such as numbers of birth per year since 1987, and a clock to indicate shift times in the working day… all gathered from conversations you and Sue had with the midwives and staff on the unit. As a measure it is full of precise and practical information but it has not forgotten in its precision the body and bodies whose lives enact the data. Some are named: as scattered across the length of ‘measure’ are the names of the different professionals who use the unit, from public health midwife, consultant midwife, community midwife, to ward clerk, consultant obstetrician, consultant anaesthetist, volunteer labour supporter, domestic assistant and medical student, to name just some. But also the body emerges in other ways, indented circles of different diameters allow us to touch the wood and register with our fingertips the size of dilation. And the lacewood itself shimmers and races in its varied striations, alive with its own internal measures of growth and movement and replenishment.

Also you and Sue had Pinard horns made from the wood to give to midwives to listen for fetal heartbeats. Themselves like tiny trees, but hollow, so beautiful to hold, must have been exquisite gifts to receive for the midwives and staff as they mourned their fallen tree.

All this, it seems to me, is very you, Julia. This combination of precision and feeling. So Yes, I feel sure I can find you in the Homerton measure. But I wonder if you might also be elsewhere in the Plane trees; if this one tree is only the beginning?

(No doubt there are other species of tree you’d prefer. The Eucalyptus maybe? That antipodean dazzler, with its bluey hues, that seems to relish in its difference. I know it was a favourite of yours. But I think I might still find you in the London Plane.)

The London Plane, like you and I, is non-native to London (and to Britain) despite its name. It is also a kind of immigrant, a traveller. And its origins are somewhat contested. A hybrid of the American Sycamore and the Oriental plane, certainly it emerged from the European Imperial expansionism of the 17th century. At that time while the Oriental plane – itself brought into Southern Europe from Asia – was well known as a tree planted for its wonderful leafy shade in Spain and Southern France, the American sycamore was native to the East coast of North America, and was only introduced into Europe when the first American colonists in the mid 17thc sent seeds back to Europe. Most likely the hybrid ‘London’ plane was grown – either by accident or design – in Spain or France at this time. However another ‘foundation myth’ that roots the London plane to London itself runs that the tree was first ‘discovered’ by John Tradescent the Younger in the mid 17thc generated by accident, in Tradescent’s ‘ark’ – the nursery garden and ‘cabinet of curiosities’ in Lambeth that Tradescent made with his father.

Tradescent the Elder travelled widely in Europe, but Tradescent the Younger also travelled three times to visit the early European colonies on the East coast of North America. Did he bring the American sycamore seeds back to London? Did he plant them near the Oriental planes he had growing in the ‘ark’, did he cultivate, or maintain, the vigorous new hybrid tree that may have grown? Maybe. Maybe not. We don’t know for sure. Probably the truth is less singular, less locatable, less proprietorial. Less a story of individuals and more a story of power and systems and plunder, in which individuals are inevitably caught up, some of whom play a larger part, some of whom suffer, and some of whom survive, make their mark, thrive even.

This was the outcome for the London plane, when the Victorians struggling to breathe in the smog and acrid smoke of Industrial London, planted Plane trees along streets and riverbanks. The trees along the Embankment and the Mall for instance would have been among the first of these urban plantings. Planes had been planted in parks and garden squares before this, as far back as the 18th century (these Planes here in Charterhouse Sq were probably planted in the 1850s) but it was only this pragmatic planting ‘en masse’ that began the greening of the city as we now know it.

The Plane tree’s success as a survivor in the pollution of London is due to its adventurous root system, its tolerance of different soils, its ‘otter like’ leaf-surface from which toxic particulates simply slide off in the rain and its clever exfoliating bark, what the Victorian poet Amy Levy described as its ‘recuperative bark’.

You knew what it meant to plant a garden – trees, plants, fruit and vegetables – in a city Julia. To come together as a community and make a garden together. You knew what it meant to make things grow, in the right way, for the right reasons.

Although the Plane trees are not exactly those kinds of gardens they too hold our city together, breathe life into it, and shelter its diverse complexities beneath their expansive canopy.

Today, the London Planes that have survived and matured from the 19th c, and the new Planes that have since been planted, sequester over 3000 metric tonnes of carbon every year. The oxygen they release, along with the millions of other London trees, is a vital lung for those of us who live here. Our city body, collectively, could barely survive without them.

If you’re in amongst the plane trees then Julia, all of them, not just the one or the clusters, I might find you each time I breathe deeply in this, our adopted home.

Later in our walk we will pass through Mecklenburgh Sq. and walk by the house of the poet Charlotte Mew. Mew was born in 1869 and in her 60s wrote a poem called ‘The Trees are Down’,

“They are cutting down the great plane-trees at the end of the gardens.

For days there has been the grate of the saw, the swish of the branches as they fall,

The crash of the trunks, the rustle of trodden leaves,”…

The Spring itself is in the trees. She writes,

“These were great trees, it was in them from root to stem:

When the men with the “Whoops’ and the “Whoas’ have carted the whole of the whispering

loveliness away

Half the Spring, for me, will have gone with them”.

Mew’s lament for the trees and the loss of Spring they harboured, ends with a protest cry ‘Hurt not the Trees’. She gives it to the angels and hears them crying out, but I glimpse in her call a foreshadowing of you and Sue, outside a hospital in Hackney, recognising that although the living tree could not be saved, its value could be shared and measured (along with the value of the life giving work done in the maternity unit) even after its Spring had gone.

Born just a few years before Mew, the poet Amy Levy also loved the London Plane tree. But Levy, I think, saw the plane tree not as a natural support system, but more as a fellow urbanite. As if she recognised in the London Plane her own ‘fin de siecle’ urbanity, and saw it as a kind of reminder, that there are those for whom the city is life – despite its toxins and hardships. Those who don’t quite fit, but who grow and shed and grow and shed and grow, can find roots here, and reach.

For Levy the reach was vigorous and brave, but short. She committed suicide aged only 27. But she grew amidst the plane trees, relishing the city and fervent in her politics, activism and desires. She was Jewish, a lesbian, a feminist, and a socialist, all of which she addressed in her writings. She was friends with revolutionary women of the time including Clementina Black, Eleanor Marx and Dollie Radford. (I wonder if as a young woman she might have crossed paths with Charlotte Mew?)

About a week before she died she made the final proof corrections to her book ‘A London Plane Tree and Other Verse’ which was published in 1889. The book contains a frontispiece showing a print of Temple Church with some young Plane trees growing outside it. The small trees are nestled in amongst the church and its surrounding buildings, entirely embedded in the architecture. A person leans against the fence to take in the scene. Levy has written across the image in capital letters ‘A LONDON PLANE TREE’ – as if to emphasise the point of the picture – not an image of Temple church, but of the trees outside it.

A few pages on is a quote that begins the collection of poems, from Austin Dobson “Mine is an urban Muse, and bound / By some strange law to paven ground.”

The Plane tree then as ‘urban muse’. I think you would like that idea Julia. I think I can glimpse you there amidst Levy’s London Plane, perhaps listening with a lacewood Pinard to her beating, fighting heart.

I’m looking for you in the plane trees Julia. And there is one last story of the London Plane I want to share with you. It is still a story about breathing and how a city is lived, and how its people are held, and abandoned. This time not in London, but in New York.

In the chapter ‘Breathing with Trees’ of Jane Hutton’s book ‘Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements’ that Katie introduced me to, Hutton discusses the history of the London plane in New York city, and in Harlem and Rikers island in particular.

Hutton’s chapter centres around the ceremonial and symbolic planting of a single London plane tree on 7th Ave in Harlem in 1959. The tree was the first in an urban scheme to plant 398 trees throughout Harlem, one every 30 – 40 feet. It was the outcome of a long struggle by Harlem’s black and Carribbean residents and activists to return to their public space an environment of optimism, health and pleasure. 7th Ave was the heart of Harlem and in the decades prior to this tree-planting it had seen both the social and cultural plenitude of the Harlem renaissance and the ongoing damage of racist discrimination and economic disinvestment, that had by the post-War era left the neighbourhood destitute.

Activist groups such as the People’s Civic and Welfare Association (PCWA) campaigned not only for improvements in housing and sanitation alongside basic civil rights, but also for improvements to the neighbourhood’s streets, many of which had lost their trees due to street widening in the 1940s. They argued that replanting trees – especially along the boulevard of 7th Ave. would be a form of ‘visual education’ for the area’s residents, restoring their ‘morale’ and ‘civic pride’, not to mention their literal health and well-being. Thus, after thirteen years of campaigning the first tree was planted. An eight-foot high London Plane, grown on Riker’s island prison nursery.

It is in the story of this extraordinary tree nursery that Hutton’s essay torques further the complex narrative of the Plane tree and its place in the intertwining stories of the growth of the 19th and 20th century Euro-American city and the people whose lives paid for this growth and grew with and within it. These are old stories given a new and rightful urgency in a contemporary social and political context in which the ‘right to breathe’ has been so violently refused.

There isn’t time to detail the story of Riker’s island as Hutton does, but in summary, she describes how the island which held Rikers prison and the New York city dump, went from being a toxic zone of rat-infested pollution, to becoming a tree nursery for trees specifically grown to compete well in the harsh urban environment (London planes being one of these species). The young trees were planted, tended and maintained by prison inmates, for whom the labour was considered a source of rehabilitation, and preferable work, as it was outdoors, physical and nourishing to the soul as well as the body. Never mind that it was still done for no pay and that when eventually prisoners did start getting paid for their labour, even up to the 1980s inmates who worked on the Rikers island nursery were only paid 50 cents an hour.

Add to this the disproportionate number of incarcerations from black and Hispanic areas of the city following the introduction of new drug-laws in the early 1970s, that were directly targeted in viscious sweeps by police throughout neighbourhoods such as central Harlem, and the Rikers island London plane trees begin to tell another story in which amelioration and exploitation go hand-in-hand.

For Hutton what is important to remember about these trees, is that, robust as they are, they don’t survive alone. They have to be grown and when planted, maintained. They will flourish in a setting of civic investment – financial and social – an investment, that while always welcome, is all too often as uneven and unequal as the dappled shade they offer.

Hutton has checked and is sure that that first Plane tree sapling, planted on 7th Ave in Harlem in 1959 is still there, outside a hairdresser’s shop. Unsurprisingly, the area has been increasingly gentrified, and its black communities pushed further and further out of the city, not least because the trees are there. But the value of the growing and the planting of that tree should not be downplayed, despite the inequities and injustices that followed in its wake.

The trees give life to the city, and more than that they stand for life in the city as a place where people live. Here in central London, after a long year of retreat and loss, it is good to take part again in the life of our city outside the home, in its public spaces, its streets and roads, and parks. Here as we stand and walk under the London Planes, so full of Summer, so full of the hope that we can make a better place, a less unequal city, I’m sure I find you Julia. I’m sure you’re here.